Here are some memories and photographs that we have already received for our project....

”My grandmother, Violet Walsh, used to tell me about taking a donkey around, with a bell around his neck delivering milk. At the age of 12, she was living at Finley Cote Farm, Hawkshaw, with her parents.“ Lynne

” As a child, I used to play with other village children on Holcombe Hill. It was our huge playground and we only returned home for meals. We also played many games on Cross Lane and Chapel Lane because it was very rare for a car to come along to disturb us.” Cath

” On Good Friday crowds people visited Holcombe Hill. There were always stalls lined up at the foot of the hill selling posies of flowers, small toys and refreshments.” Cath

”I remember clothes regularly hung out to dry on the two ”drying greens“ in the village. One was between the Shoulder of Mutton and the Old Post Office and the other was next to number 2 Helmshore Road.” Cath

Merchants Row, Lumb Carr Road around 1967.

Herbert hay making in Holcombe

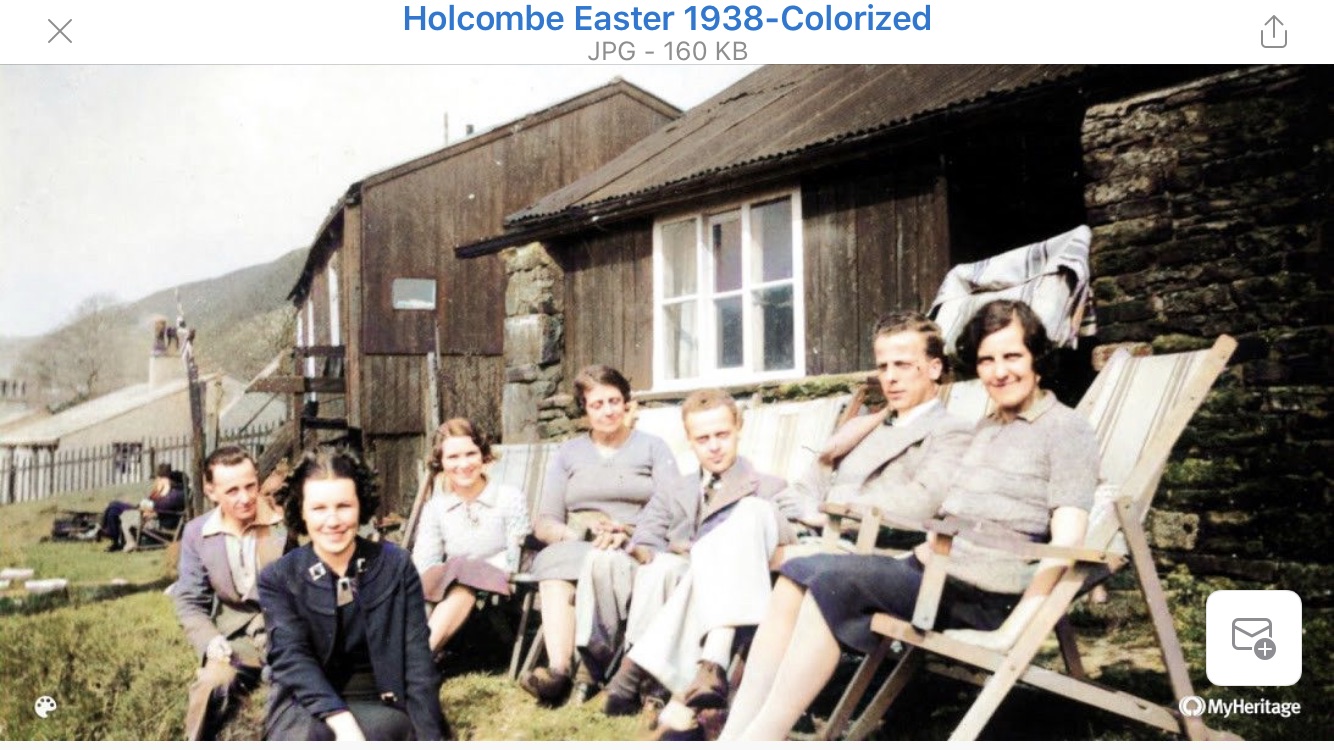

These are some very interesting photographs sent to us by Howard Barton. He and his family spent some of their holidays in the Holcombe Valley, in the wooden chalets shown in the photographs.

Cottage on Moorbottom Road c.1948. Standing Florence, centre daughter Marie, together with daughters-in-law and grandchildren.

Cottage on Moorbottom Road c.1938 Florence with her twin sons Geoff and Ken, daughter Marie, son Stanton, two future daughters-in-law. Stanton died at sea, serving with the Royal Navy in 1942

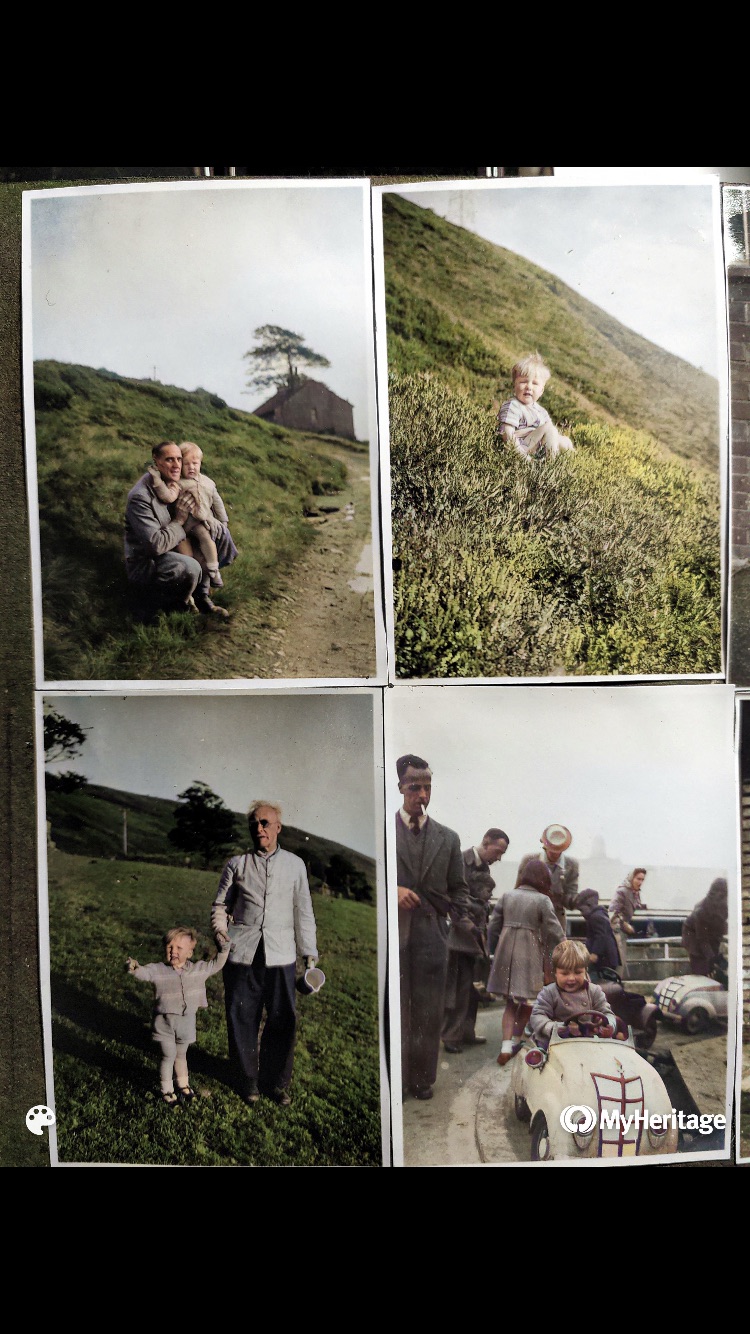

Howard Barton with father Terry and Grandpa Charles c. 1948

Howard Barton with Grandpa Charles

Here are some photographs of Holcombe Village sent to us by Kay.

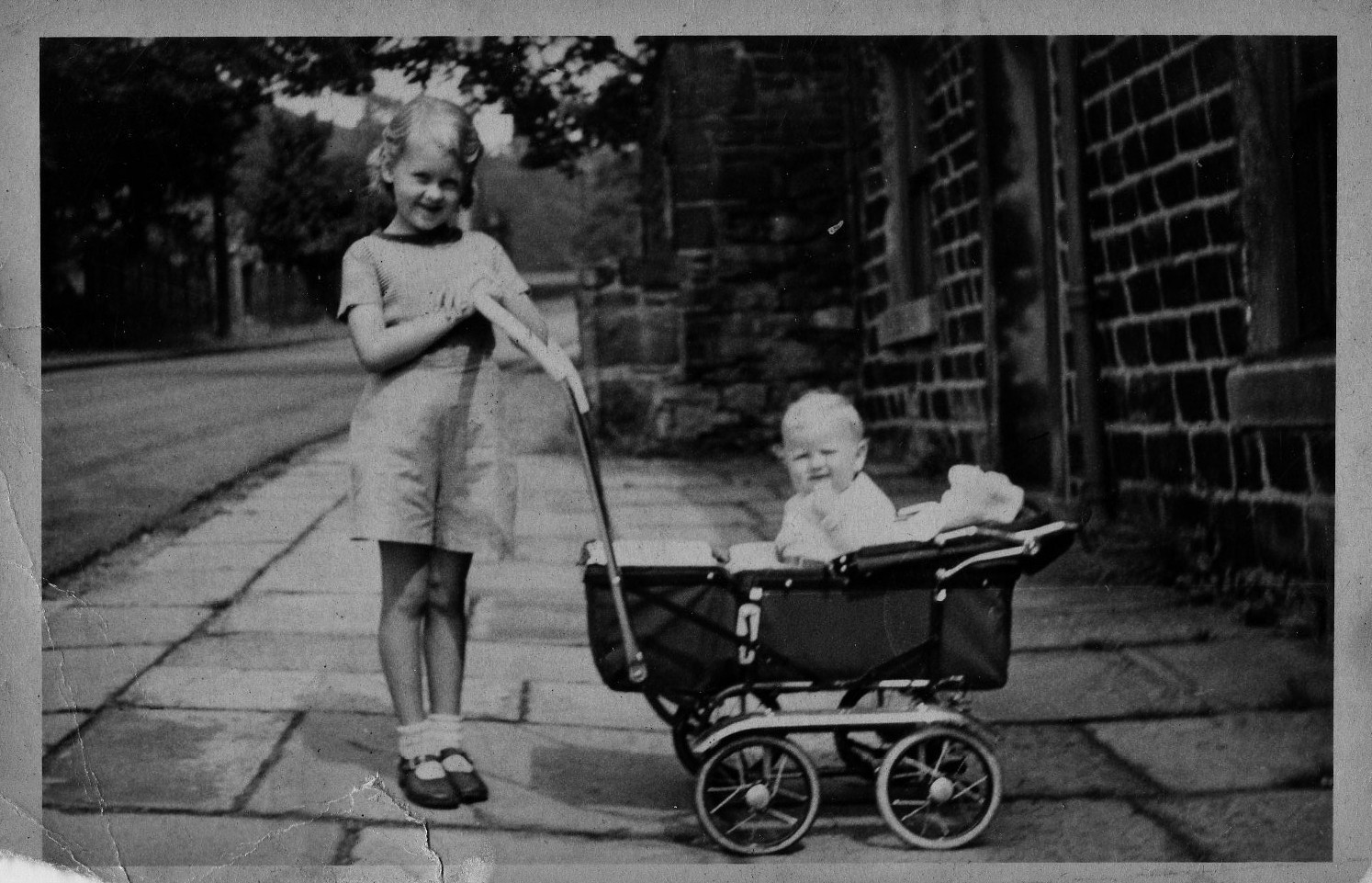

Greg and Kay Wallbank c.1953 on Lumb Carr Road

Holcombe C.E. School

Holcombe pantomime 1956

Holcombe, with Herbert - Kay's grandfather Herbert haymaking in Holcombe

Jimmy Cotter and Kay Wallbank on Lumb Carr Road

Merchants Row, Lumb Carr Road, c. 1967

The Starkies of West Mont, Maude Starkie, nee Pie second on left, James Starkie third on left

Memories from “Local Lad Jim”.

These very interesting memories were written by Local Lad Jim. HMHG would like to thank him for taking the time to record his memories of life in Holcombe when he was at primary school.

“I was at primary school in the late 1940s and 50s and can easily remember the world then in great detail and colour with all the smells and tastes that my mum and gran could provide from the kitchen. I had a wonderful childhood with great freedom to play outside with school mates and others who joined in the fun.

In the late 40s I attended the school at the end of our street, but my playtimes were slightly curtailed when I was ill for a large part of 1950. I stayed at home and played old 1930’s gramophone records.Some were popular classical but many were jazz . The old wind -up gramaphone eventually expired to be replaced by a Dansette record player . which played 45‘s and 33 rpm records . My first record purchase was Jailhouse Rock by Elvis but my Gran put her foot on it and it broke . Upset was hardly the mood of the moment. My two brothers and I used to play cricket in the street, coached by the famous Ramsbottom Cricket Club professional who lived across from us. He also provided bats and tackle and one old bat was signed by the cricketing wizard Learie Constantine. I wish I’d kept it. My two brothers were good players and we often used to go to Saturday matches . My eldest brother had the occasional job of score keeper and posted number cards on the side of the box. This box was an old horse drawn gypsy caravan with no shafts , carved scalloped frame, painted green. We had a long pole with a large net on the end to hopefully retrieve balls from the River Irwell . The scores for six were not that often and many a ball was declared lost . The cricket ground was a notorious sun trap and many wore the knotted hankie to prevent sun stroke . Drinking tea or anything wet was essential .

Our street had a mill at one end which made fine copper wire for electric motors and a “pop” works – Giles Taylor, maker of fine mineral waters and provider of TEMS potato crisps. The crisp packets of grease proof paper had a drawing of the Peel Tower on them. These delicious crisps were truly great when washed down with Dandelion and Burdock “pop”.

Behind the mill or wireworks, fields extended up to Tagg Wood and cows were driven to pasture in the mornings and back in the afternoons, along the street. Garden gates were always kept shut as roses are tempting to cows.

At the other end of the street was Hazlehurst Primary School, also surrounded by fields. Cows grazed, and later grass was mowed by the farmer, Bobby Johnson, who worked the farm on Little Holcombe. That is the lane between Geoffrey Street and Lumb Carr Road. Before he got a tractor, he had the most enormous great shire horse which did everything he needed. But, it grew so large he couldn’t get it in the shafts of many carts he had at haymaking time . One was long like a lorry with four wheels and lads would throw up bales to stack so they wouldn’t fall off . “ Dobbin “ the shire’s name , was fit for the job with apparent ease .Bobby eventually decided to sell the big shire and it went to a fisherman in Morecambe for shrimping in the shallow waters of the Bay . Demand for little brown shrimps was great . The fashion still remained for shrimps to be served at afternoon tea at weekends . My Aunt Clara used to present them on lettuce leaves on a lace doyley on her best china . Victorian niceties still prevailed in the 1950 ‘s . Dread the thought but as teenagers we used to knock up a hot shrimp curry on a Saturday night when parents were out dancing . We had to raid the medicine cupboard for olive oil BP which was all we could get . It now seems sacrilege to use delicate tasting shrimps in this way and of course olive oil is commonplace .

My school headmaster was Mr. Boardman who was my uncle’s wife’s father. He was a stern but kindly man and I was given the job of paper and jam jar monitor. The two air raid shelters in the school yard were the stores for this collected paper and glass. Re-cycling was a part of life then, as now. At haymaking time, the school was seemingly overrun with mice. As I recall that as we sat in a ring on the hall floor for music, a band of field mice would join us and run around, too. But, the main reason for living was to play out when all jobs were done. In summer time and especially in the Hols we could play out till 5.00 pm and would never be late home for tea. The penalty for being late was dire and we all knew it. Strangely, for kids, we never were.

Behind the gardens our street had land for keeping hens and other poultry. My mate’s dad, Tom Pilling, kept hens and Eric and I would look after them in the summer. We fed and watered, cleaned perches, mucked out and collected eggs. We creosoted wood and did other nice jobs. One afternoon in warm weather we came home to find ourselves covered in small red mite spiders, itching and making us red too. Without any ceremony, we were stripped naked by our mothers in the yard, stood in a tin bath of cold water and scrubbed with carbolic soap. We both howled! No doubt Eric’s dad, Tom, may well have had some chastisement when he came home from work from Lily, his wife. Tom kept small bantam cocks to keep the hens happy. He had more than one or two battles to keep the peace as these blighters would fly up to peck his face. A bat with a flat cap is no deterrent to a “banty” but Tom’s deft ring of the neck, was. One year, Eric and I decided to dig a hole to Australia in their back garden, with his dad’s approval. We dug it so deep that we were lost from sight and needed a ladder to get in. The rain brought an end to the Australia trip and we filled it in.

Another neighbour, Jack Beckett was a tackler at Cobden Mill and drove an ancient Lanchester limousine (1933) to convey Billy Eccles, the mill owner, home. He lived on the main road and couldn’t park the car there. Jack often let me drive the old car up the street, sitting behind the wheel on his knees. The windscreen was bright orange as apparently the early safety glass film had failed. The car smelt of leather and sweet petrol fumes, definitely a health hazard. There were a few old cars kept in wooden garages down by the wire works. One chap had a huge Sunbeam with a straight eight-cylinder engine which he struggled to start up. It was like a 1920s American Al Capone car with a small oval window in the back cab. He never ran it, but we all wanted it.

My Uncle’s three wheeler Reliant van was very small but by some means he managed to squeeze his wife ,his sister [ my Mum ], my Dad , and three lads into it on a Sunday afternoon to visit Barton Dock swing bridge on the Manchester Ship Canal . This was a great attraction for many as large ocean going ships would pass by with bananas or fruit cargoes. Officers in uniform were on the bridge and waved at the crowds. The ships were well painted and polished smart, flags flying. There was a shop in Eccles that sold fish and chips even on a Sunday and these would be eaten on the way home . It seemed a long way. We sometimes sang Harvest Moon and One Man Went To Mow but favorite was Show Us The Way. It was simple family fun and we nearly wet the floor, laughing.

Our local motor engineer, Lionel Millmore had a Bond minicar. It was a three- wheeler with no reverse gear. He used to pick it up by the front bumper and trundle it around through 180 degrees if he wanted to turn it around. I think they were made in Preston, very cheap and tax free. Just across from the garage was a pop bottle mountain of broken glass thrown out by Giles Taylor. This stock of glass contained glass alleys from bottles from before the first war. They were good to replenish our marbles collections, but care was needed that we didn’t cut our pumps or wellies. It wasn’t that dangerous, we didn’t think.

Summer afternoons were mostly for playing marbles (or conkers in Autumn) and throwing arrows. Arrows were made with nails and black tar from the road sets fixed to the end of a wooden dowel. The fletchings were from a Joker playing card. With a launching string notched below the fletch, a flight could be the length of the street. I don’t recall anyone being hit, but no doubt it would have been lethal. Bogey making was a joint effort by lads, acquiring suitable bits like pram wheels and wooden boards. A nut and bolt to hold the front axle and swivel was a major problem. Drilling holes in wood was by a red-hot poker set up in the living room fire and whisked away when mum wasn’t looking. Our track was increasingly hazardous and fast around the street and side lane, so it was transferred to the long grassy hill by Tagg wood. We constructed a ramp for the bogey to be airborne for a few seconds. This efficiently bent rear wheel spokes or flattened wheels altogether. It was an early version of Red Bull Soap Box Derby, now so popular on Sunday morning channel 4 TV.

Tagg Wood was, by far, the best playground. We often used our bows and arrows in battles of cowboys and Indians. Indians always lost as the arrows just vanished in long grass or high up in tree trunks. We constructed a dam out of grass sods and stones across the stream, and this pond enabled us to sail model boats and rafts at which we would hurl stones and clods. Pitched battles of one sort or another were inevitable. Expecting models of boats to be destroyed I started an interest in model making. Amongst other craft I worked on a model of HMS Bounty which took years to complete with masts and rigging. My Uncle Don made me a model of his ship MFV 1108 for my eighth birthday which I still have. It has sails and fittings and he took it from Peterhead in Scotland to Colombo in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, as a convoy escort. It was sold to the Indian Navy in 1945. The model hull was carved out of a solid piece of teak which he brought home . He sadly died as a relatively young man . He became a dyer at the BDA on Bolton Road West and instilled a lasting interest for me in ships and the sea. Auntie Anne entrusted to me his 1939 Channel Pilot and his Roamer watch but both wouldn’t help anyone these days.

The older we got, the more daring we became, so we had short visits to adjoining streets. Annie Street had a large stone walled building which turned out to be an old abattoir, just like a fort or castle, obviously no longer in use. But it had a large open yard with lean to buildings around the outside, a large wooden gate and sneaky ways in and out. What a dangerous place for kids!

Full expedition gear was worn on these visits to the fort. Bows and arrows, wooden swords, old binoculars, Smith and Wesson 45 cap firing pistols – the lot. This was the most exciting place for us adventurers, all but, short lived. The place was demolished, and houses built on the site – spoil sports.

By the early 1950s we had graduated to longer stays away from home. An early start with packed lunches and a bottle of pop were allowed providing that we were back home to tea at 5.00pm. There were strict “no go” areas to be observed. No water crossing, no messing in mill lodges (well, most of us couldn’t swim anyway). No going to the River Irwell or the railway. No going into Redisher Woods and lodges. As a choir boy at St Andrews Parish Church, Nuttall Lane, it was my sad experience to witness one of the boys ending up in a box in the church chancel. Our friend had drowned in Redisher Lodge and we had to sing at his funeral. This event was too tragic and affected our playing out activities for ages. Being a choir boy from the age of six was a serious job. The incumbent was Canon Williamson of the traditional Church of England, liturgy was celebrated with emphasis on singing and long sermons. Psalms and anthems required repeated singing to be correct, at the Thursday evening’s choir practice. Our choir master was the local butcher, Ted Carr, who conducted us and also played the harmonium. The big church organ was only started up for Sunday services or feast days at Christmas, Easter, Whitsuntide and the sermons. We wore the cassock and surplice at all times and mums were asked to wash and iron our white surplices for special services. Ted Carr paid us once a year, about half a crown, and he also took the choir boys and men of the choir to Blackpool Tower Circus. This was the event of the year and we went by coach. Boys had “pop” and the men had crates of beer secretly stowed at the back seat. The circus was the most thrilling and exciting spectacle for us as we were always seated at the front by the ringside. There were mad clowns like Charlie Cairoli and the white faced clown who had a car that fell to pieces – hilarious! Acrobats and high wire acts frightened us to death, but the prancing horses and lumbering elephants were nothing compared to the lions. The beautiful, powerful cats were displayed behind a quickly assembled cage around the centre circus ring with tunnels to let them in and out. The lion tamer was flashily dressed in jodhpurs and polished boots, big white shirt and slicked back hair. He had a stick and chair to instruct the lions to do various moves. The lions were always snarling and trying to hit him with their enormous paws. All this was taking place within six feet of our seats, very exciting.

Whitsuntide was another event in our choir calendar requiring polished shoes and white surplices. Churches of all denominations walked parish boundaries and main streets. Visits were made to places like old folks’ homes and the cottage hospital, and we sang to the accompaniment of a brass band. The Whit walks had parades of bands and organisations like scouts and guides and cubs in full uniform. The town was full of people in their Sunday best clothes enjoying the sights usually in fine, summer, sunny weather. Each church had its own banners of huge embroidered cloth, often with gold fittings and silk ropes. These banners were held up by two strong lads and the guide ropes were managed by four of the church’s most pretty girls or should I say young ladies. If a wind picked up, the huge banners took some handling. The brass band and in the case of St. Andrews, the pipes and drums of a Scottish band from Stalybridge, gave everyone the chance to march and swing arms. But not us choir boys – we were “clergy” and had to break step and shuffle, by order.

Carol singing on Christmas Eve was an annual duty when the choir would visit elders of the church, usually wealthy, who would ply the men with sherry and mince pies and boys with “pop” and crisps. By the end of the evening the boys were feeling sick and the men were not walking straight. The men were always kind to the youngest boys and confided the secrets of the night sky, that the shooting stars were proof that Father Christmas was about.

The wanderlust could be easily satisfied by one mile or two-mile radius rambles from our Hazlehurst homes. Making a map of Holcombe Moor and Red Brook became a “business” and the long summer days gave us opportunities to explore and often just to stand and stare. We liked to sit amongst the rocks by Top O’th Moor Farm watching rabbits and we sometimes watched the activities down below on the rifle range. This area of shooting and explosions was a danger zone and signed by red flags as a prohibited area for access. But we could and did watch from the top of the moor with fascination. By walking further north towards Red Brook we observed soldiers like ants, running back and forth discharging mortars and sending plumes of smoke and earth vertically upwards into our field of view. This must have been hundreds of feet. More of these demolition exercises carried on further towards Red Brook and the remains of Holcombe Head Farm.

The rifle range was a source of noise and lights on occasions. Parachute drops and low flying aircraft were seen even from our house and night time firing of guns fairly common place. I recall a Spitfire flying down our street low enough for me to see the pilot. That would have been about 1950 or so. Exciting or what? Aircraft were part of our family life as our Dad worked at AVRO’s in Chadderton in the drawing office . He used to bring home the Eagle comic each week for us to read about Dan Dare , Pilot of the Future and the dreaded Mekon . Gripping though it was and so futuristic , it was quite believable to us . Part of the comic had cutaway illustrations of aircraft , locomotives and other huge machines . Our Dad’s work involved doing drawings for the Vulcan delta wing bomber , amongst others . He would sometimes bring preparatory sketches home for us to look at . But the Eagle comic sometimes arrived rather dog eared as it must have done the rounds of the drawing office before we got it. Engineering to many kids was normal as many parents had and were continuing to work in those industries . I think the comic was a local effort from Manchester and Lancashire but no doubt Google will know more . The later space exploration and moon landings were no surprise, possibly disappointing as the Mekon was not involved . I was fascinated by the Dan Dare world of design and colour and the prospect of international government and peace.

The land adjoining Moorbottom Road to the west was worked by a number of farmers occupying near derelict buildings. Even as lads we could see the struggle to turn over the ground. Men worked with big petrol driven cultivators with rotating trowels. Tractors and ploughs were not suitable we supposed. It looked hard graft and the fields were small and full of stones. One of the houses was a fairly modern, two-storey brick and render construction, but in poor condition. Each farm had a wind generator to pump water with bladed vanes about 1.5 metres in diameter and set up on Meccano like pylons. We were told that some of these men occupying the little farms were demobilised from army service after 1945, trying to make a living.

By the end of our primary school days, a group of us would arrange an expedition to find the hermit who allegedly lived in a cave west of Red Brook. Also, to find the source of Red Brook by Black Moss and Wet Moss. Bull Hill was our limit or range at two miles from home. The quickest way across Holcombe Moor was by the wet boggy ground. We tried to map a route across this bog which was dry-ish. You can see the top of Peel Tower from Pilgrims Cross. The path was almost a straight line with White Hill and Harcles to your left. I recall making this way back in poor visibility when the weather caught us out. We were late getting home, and mums were not pleased with this adventure and we were grounded for a while. But, a good experience, none the less and we all learnt a lot. I suppose reading the Arthur Ransome books and Enid Blyton’s “Famous Five” gave us a false confidence, but we had great fun.

The summers seemed always to be blue sky with cotton grass in white fluffy tufts everywhere. Skylarks were calling, and another similar bird called a Twite, which fly up on the high moors. Red grouse were present in small groups of five or seven with their familiar croak. These were left from the old grouse shooting days much favoured by sporting gentlemen and mill owners. Sitting on the side of the moor over looking Red Brook gave us an exhilarating view of land which had much less tree growth than now and it was easy to see wild life as if you were flying. The wind in the long grass just before mowing was always a sea of greens, constantly moving. How fortunate we were to have such freedom.

Hey House was a source of great mystery dating from the C17th, 1616, as the King’s hunting lodge and the alleged site of Holcombe chapel with its small bell cupola. In fact, Holcombe chapel was on the site of the rectory demolished when Emmanuel Church was rebuilt in the 1850s. The bell cupola probably came from the old chapel. Hey House also was supposed to have a cut off tree as a table, in one of the ground floor rooms, very ancient but no longer growing.

The man who lived at Norcott, next door to Hey House, was making alterations to the house and often chattered to us. He was a dentist by profession and had an interest in local history. He told us of his findings in the house which seemed to him indicating a hostelry and perhaps an inn on an old stagecoach road. A halfway house between London and Edinburgh. One can easily slip into the myths and legends of hearsay, but, to us kids, the thought of highway men on black horses along Moorbottom Road on a dark windswept afternoon seemed plausible enough. When he went on to declare finding two longbows wrapped in oiled cloth in the eaves of his barn, we were hooked on tales of the past and an interest in local history began. True or untrue didn’t matter.

A little way down the road from Hey House was the Aitken Sanatorium [ now the Darul Uloom ] which served as a TB hospital and patients were housed in wooden cabins which had verandas for beds. Fresh air and plenty of it was the cure offered but the practice had stopped in post war years. The huts were vacant and overgrown. The small swimming pool adjacent had become full of weeds, but it was a great place for sticklebacks and newts.

One of our last escapades came about as we neared the top class at school. It was the winter of 1952 when we had a heavy snowfall for ages. We made igloos in the field and snow was 18 inches deep and came well over our wellies and knees got chapped. (All boys and girls wore shorts or skirts – no long trousers till 15 years old). We didn’t seem to notice the cold.

One of our mates had a 4-man (boy) sledge and he lived at Hill End House on Moorbottom Road. The snow had effectively stopped everything from moving, anywhere. We carefully planned a sledge run from Moorbottom Road between Hey House and Norcott down to the main road – Bolton Road West. We knew that this was a long run with all sorts of hazards but off we went – a fast start off a steep slope put us just on Hey House gate post, down the steep lane past the sanatorium, past the gate house with all brakes on to cross Lumb Carr Road and to just miss the gate post to Little Holcombe, past the farm to the end of Butler Street (where I lived) on to Geoffrey Street and ending at the gates of Hazlehurst House on Bolton Road West.

No traffic was encountered as there wasn’t any or persons either. No boys were hurt or lost, and we set off for another return run. But, we were all knackered and went home. Smiles all round.

By 1954 all primary school play times had ended and grammar school life brought new challenges.”

Memories from “Local Lad Jim” — part two, secondary school and beyond.

It seems a long time ago now that I start to recall, but Ramsbottom was still an industrial town with cotton spinning and weaving mills and the attendant engineering works that they required. The railway and the endless noise of shunting waggons prevailed most nights even though we lived a mile or so from the town. It was an Urban District Council until 1974 and the largest one in the country by all accounts. It was not a village by any standards, and it still rankles me when I hear today’s people refer to it thus. It was a busy, bustling town with all the shops and services that one could wish for except on Saturday afternoon in summer when the entire place stopped shut. Cricket in the Lancashire League was the passion enjoyed by everyone and packed the ground to capacity.

The change of school from Hazlehurst to Haslingden in the mid-1950s required great effort and initiative compared with the dash to the end of the street. The early rising to walk to the railway station, the journey by steam train to Helmshore to catch the school bus to Haslingden with boys and girls that I hardly knew took some getting used to but soon settled into a routine. The old grammar school, as it was then, only had about 350 pupils including a sixth form. Boys and girls came from a wide area being a county school. The head teacher was the formidable Arnold Weston who ruled to extreme high standards. He was proud that each year a handful of sixth formers went off to Oxbridge colleges. Children came from a wide background of skills and talents, but parents were not encouraged to participate in the education process; the complete opposite of today and the homework culture. Many of the staff had wartime experience of service life and with hindsight I can identify the disciplined attitude which they often used. Public floggings were not too regular, but they did happen on occasion. Some of the kids had a poor upbringing probably from lack of parents or parental control and brought up by grandparents or an auntie. Bullying was an issue that was not tolerated. By today’s standards staff ruled harshly but fair and the turnout was clearly good. I hated school, and Latin seemed pointless. I couldn’t understand why you were put down all the time and nothing explained. Work hard, head down and you will pass the exam even if you were killed in the process. Joking apart, some staff were very amusing, even funny at times.

Our physics master had a habit of playing with a hand grenade during lessons if boys on the back row were troublesome. He would throw it up and down from one hand to the other and, just to emphasise a point, take out the pin. This trick certainly aided our concentration – success. It was a couple of years later that we found out that the grenade was a demonstration dummy from his army days.

All staff wore black gowns in school except our art master and gym master who also taught us woodwork. As the school was so small, it had to rely on renting the upper floor of a Methodist Chapel in the town which contained work benches and tools. There we were instructed in planing, sawing and jointing a huge variety of timbers. Lathes, pillar drills and band saw were at our disposal with little emphasis on health and safety. Cut yourself at your peril. We produced all manner of useless and occasionally useful stuff.

When declared “handy” you may join the canoe making group which was involved in producing a framework twenty feet long to hold ply wood panels with fibreglass joints or calico, liberally coated with dope. This latter technique was used in first world war air craft construction. The air was thick with evaporating fumes. Evacuation was the only relief, so we were directed to sorting the wood store.

Our teacher was a very liberal minded free and easy chap, perhaps a bit more than was safe as he unfortunately started a liaison with our head girl and two became three. This matter caused huge consternation in school and of course both were asked to leave, the shame of it! We thought it was great, lucky man that he must be. He got a job in a quarry in Ramsbottom and served hard labour. All part of our learning of life, one may now say.

On the other hand, our art master, Neil McTaggart was a refined and cultured person and instilled an interest in music and drama as well as art and history of art. He always carried a book in class to teach himself a language, French, Italian, Russian. He was well travelled also, tanned and wore linen suits and Chukka boots. He had numerous lady friends who were alleged to be platonic, whatever that meant. Of all the teaching staff, Neil McTaggart encouraged me to go on to Manchester school of Art and Design to study architecture. Keep a wide and enquiring interest in all things, was his advice to everyone.

Our history master could easily be classed as a martinet. He would pace the corridors barking orders at people, gown billowing in tumult, truly frightening. Essays were produced on time with no deviation of subject. No waffling tolerated. There were weekly finger nail inspections and further orders to “get your hair cut”, girls were simply glowered at. I reckoned he was scared of women, but very many years later I found out that he had spent the full six years of the war at sea, in charge of a minehunter in the North Sea, without coming ashore and on a diet of barbiturates. That may just have affected his personality. He found that I had an interest in architecture and asked me to explain the Gothic styles of Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular windows. This set me in turmoil. A mix of delight and fear in presenting to my school mates something not a part of school life. A large part of the lesson period was given to me with access to the blackboard to draw examples. “Being thrown in at the deep end” may be the likely phrase. This turned out well for me and earned very small respect. Another lesson, if different, learned.

Other lessons were learned in out of school jobs. My uncle had a grocer’s shop and had customers from mill owners to jobless. He stocked a wide variety of food, much like the Deli of today. The wealthy clients like the Porritts required unusual things like canned Epicure smoked oysters or pheasant and continental cheeses. At Christmas time the cellar of the shop was packed with hams, fowl of all kinds hanging ready for dressing. Knives were sharpened every Saturday afternoon. I had to turn the grinding wheel which was set in a water bath. My uncle was a perfectionist and tested sharpness by shaving his forearm. I learned to clean and dress fowl and bone sides of bacon, all to be presented perfectly. Large hams were boned and packed with brown sugar, trussed and cooked. We often went to the bacon and ham curers in Bolton to select the meat floating in curing brine.

Bartering was part of shop life and some of the Polish and Ukrainian customers had no jobs and no money but kept hens. Black rye bread and Sposka ham was exchanged for fresh free-range eggs and a very satisfactory arrangement it was, too. These people were called D. P.’s (Displaced Persons) but when finally, they got jobs in the mills they became firm friends and customers. Orders were delivered on Thursday evenings in a Reliant three-wheeler van which only had one seat for the driver. I would ride sitting on a box. The odd customer did not pay the weekly order book and we had to stake out the offender till lights came on in the house. We would then bang the door till money was “coughed up”. The common currency then was the white five pound note which was huge and had copper plate writing. My uncle had a special folding wallet for these notes which he kept chained to his belt. I was paid 10 shillings a week for the shop work which taught me serving behind the counter, chatting to elderly ladies. I wore a long white apron, white shirt with sleeves neatly rolled up. Hands always spotless. Butter came in large beechwood barrels and had to be weighed out in 1lb and 2lb packs wrapped in grease proof paper. Other foods were weighed out in different coloured bags for coffee, raisins, prunes. Tea came in large tea chests for weighing out, which was always to be spot on. The weights and measures inspector may check up at any time. Responsibility at every turn.

A more lucrative job emerged at the wire works at the end of our street and this entailed clocking on and off. We worked here for the summer holiday period of six weeks. It was very hot in the mill and the air was thick with fumes from the shellac mist through which all the thicknesses of wires had to pass. The wires came to the mill as quite thick copper rolled on to large bobbins about 1 metre diameter. These were handled by fork lift trucks off the transporter wagon into the annealing department. Copper was heated and passed through diamond dust coated dyes to become thin enough for various grades of armature wire for electric motors. When graduating from cardboard box maker to fork lift truck driver we enjoyed untold freedom. We used to race the trucks around the ware house at lunchtimes – great fun until a crash occurred and one spool of wire was damaged at obvious cost. The driver lost his job but thankfully it was not me. Another lesson learned.

One of our merry band at school was from Summerseat. This place had the greatest concentration of Teddy Boys (Teds) in the world. They were all hard cases and trouble. Our “mate“ Barry Bowell had been brought up by his grandparents who lavished money on him to keep him in order. He successfully surrounded himself with protection gear in the form of Gestapo helmet, swastika armbands, a Luger automatic pistol and a Norton 500 with which to come to school. What a great character to know but he was eventually expelled for insubordination. He knew everything, yet nothing to do with school. I wonder what happened to him?

A number of us tried and tried to get into First Team cricket and football teams but to no avail. Mostly I suspect that we weren’t good enough and came from Ramsbottom. So we negotiated to be absolved from morning prayers if we ran the three miles over Cribden Moor (just behind school) instead. No missing a run each day or the privilege was lost. Only shorts and gym shoes would be worn in summer and winter alike. Fitness levels soared and a fitter bunch of lads you couldn’t find, much to the distain of the team players.

The travel by train every day was not quite like present day East Lancs. Railway, with shiny polished locomotives and clean carriages. Our steam trains were covered in black soot and windows were mostly brown. The stations were the same and with hindsight the end of an era was presenting itself. Trains were always on time and were never cancelled. British Rail were the power behind rail transport and they started to run the small multiple two diesels on our line. The morning trip to school on Tuesdays was highlighted by a full unabridged recount of the radio programme “The Goon Show”. One of our mates, Peter Lucas, had the ability to remember the entire radio programme complete with accurate voice presentation of all the characters. He was such a professional showman at the age of thirteen. We used to gather, about fifteen of us, in one compartment with some sitting on luggage racks. Legs or bottom.s were jabbed with compasses if in the way. This was entertainment at its best as far as we were concerned. He was a bright if puny lad and his mum sewed his old Liberty vest into his football shirt to stave off the cold. He would stand near the touch line in a football match and shiver, never kicking the ball; what an embarrassment for the team. His weekly performance saved his bacon. He left school in the third year as his father had a new job elsewhere, but Peter went on to the heights of Oxbridge.

The cross country contingent became enthusiastic cyclists, if only to get from one town to another for nothing. The collecting of various bits of bike and the rebuilding into lightweight racing machines became a passion and a lasting interest. One of my machines, Henri le Coq, was fixed gear, and on a solo trial to Clitheroe and Pendle Hill I must have crashed. I found myself pedalling up Manchester Road from Accrington realising blood and dirt on my left leg, side and arm. Managing to get home, my parents fortunately being out, I put myself into a bath and reflected on the ride. I had lost several hours, well at least four, of complete memory loss. Consequently, solo riding was stopped, and it took ages to recover the confidence to ride again. Groups of five or six would go up to Windermere for the day or the Yorkshire Dales. The Trough of Bowland route to Arnside was a favourite ride as it resembles a mountain pass in the Tour de France. We sometimes joined West Pennine Road Club’s east to west coast hard pack for a bit of training. About forty miles in the Dales for a ten mile time trial of a Wednesday evening now seems excessive, but so does the 150 mile round trip to the Lakes or Chester, in the day. Three of us made the decision to go to Paris to watch our hero Alan Ramsbottom from Huncoat R.C. ride to finish in the Tour de France in the Parc de Prince. That was about 1961 when we were in the lower sixth form. We went by train from Ramsbottom to Gare du Nord, Paris including the Calais/Dover ferry. One ticket, return. No fuss and very matter of fact at the ticket office. The three weeks of cycling in France cost me the huge sum of £30. I had to sell my Freddie Grubb track bike when I returned, but it was worth it, just. Our appearances began to change and we grew beards and had short Rick Van Loey haircuts. I got thrown out of the Louvre for looking like the Baader- Meinhof gang reject. The Parisian street cobbles were lethal, being very smooth and shiny. We hit a patch on a bend near Montmartre and crashed in a pile of arms, legs and bikes. We came to in a white world. Our packed sugar had been thrown high in the air and spread all around. A restaurant chef came out and poured Cognac down our throats to revive us. When we recovered, he asked for payment, but we managed to repack and scarper, to camp in the Bois de Boulogne

My school days had finally come to an end and I could start on another adventure.

This memory was submitted to us in the past by David Knowles.

”During the present political discussion relating to the proposed privatisation of the existing bur service, my thoughts went back approximately sixty years, at which time a private bus service existed in Hawkshaw.

It was after the First World War, 1914-18 that the age of mechanical road travel came into operation. The one in mind, in which I was interested, was started by the Taylor family of four brothers, George, Edgar, Fred and Tom. George was engineer for the local bleach works at Two Brooks, now demolished. Edgar was an electrician, Fred a mechanic. To start the garage business the cottage and outbuildings situated between Wolves and Lodge End was obtained. The other brother, Tom, was to take charge full time.

The first vehicle to be obtained was a Ford car, commonly known as a Tin Lizzie, this did a lot of work as a taxi, and I recall one incident. On a very wet morning a good customer (Miss Hoyle who lived at Rose Cottage) rang the garage for the taxi to take her to Holcombe Brook station. Unfortunately at the time, the canvas hood, owning to damage, had been removed and when the taxi arrived, Miss Hoyle flatly refused to get her new hat wet. The outcome was that the driver tacked his overcoat and other items of clothing to the ash frame, and eventually took her to the station. It was indeed funny to see the Ford go through the village with the coat sleeves flapping in the wind.

The demand for road travel was increasing and a Garfield 14 seater chara was obtained to to carry passengers between the Tonge Moor Tram Terminus and Holcombe Brook. Gradually, as the demand increased, a regular service was started. Day trips to the seaside were becoming popular and Taylor Bros charas were in great demand. They now had 28, 20 and 14 seaters for hire. The A.E.C. 28 Static charas had solid tyres with a speed limit of 12 m.p.h. All the charas had canvas roofs and many times, if it came on to rain, passengers got drenched before the hood was drawn over. To go to the Lakes, one had to leave at 6am, due to the speed limit. During holidays and weekends, I generally drove the A.E.C. 28 seater. I enjoyed this for two reasons:-

There were here two days when the queues formed, they were Good Friday, when thousands journeyed to Holcombe Hill, and the other taking passengers from the Royal Oak to Holcombe Hunt Races at Harwood. Relating to the existing bus service, Taylor Bros were dealt a nasty blow by Ribble Motor Co. who obtained permission to run a service from Burnley to Bolton town centre. As Taylor Bros could not compete with the Ribble, the service was withdrawn.

These memories of Hawkshaw are from Edith Coates

”Were they really the “Good Old Days?” I think anyone who looks back on times past remembers mostly the happy times, so that to them they really were the good old days.

My first recollection of Hawkshaw was of starting school. Living at Boardman‘s Farm, a mile from the village, Hawkshaw must have seemed the big wide world to me. I began in Mrs Paterson’s class, and recall how, with her pince-nez spectacles, she would read to us at home-time the story of Peter Pan and Wendy, a story that stays with me to this day. We children, who could not get home to dinner, had our dinners warmed for us in the old black gas oven in the corner of the infant room. Or twice a week we visited Mrs Barlow’s chip shop across the road for one penny worth of chips, and I must say we got a fine plateful for one penny. This, together with a slice of bread and butter, made a good meal. After Mrs Paterson, came Miss Holt (later Mrs Reid) as teacher of the infant class. Then onto Mrs Mather, who taught us the three ‘R’s and ruled with a rod of iron, or should I say a good tap with a ruler?

Everyone wore clogs in those days (except if you were posh). Ever heard of Lowry’s “Sparking Clogs.” We used to spark ours on the pavements in Hawkshaw. We often had a clog inspection by Mrs Mather, and Leslie Hayman’s clogs were always the shiniest because his Grandad undertook the job of cleaning them every day. When the clog irons wore out, we would go to Jim Haslam’s cloggers shop in our dinner hour and have them re-ironed for sixpence.

Then we went into Miss Stott’s Class, and then to Mr Almond’s where we stayed to 14 years, unless we won a scholarship. Where did the Scholarship Board, where the names of those who had won scholarships were proudly displayed, disappear to?

I must mention the Christmas treat we had at school. Every Christmas a messenger arrived from Croich Hey with a gift from Mr Whowell, a little bag containing an orange, sweets, nuts etc. for each scholar. Such a delight for us!

The main road through the village at that time was not very busy. Not many motors on the road, mainly horses and carts, and we would play top and whips during the dinner hour. The road was usually very smooth, and we got quite annoyed when the machine came with the tar and pebbles to mend the road. We could not play until it wore smooth again. We used to pin cigarette cards on the end of sticks and run against the wind with them, seeing them twist round like pinwheels.

My memories of Lent and Ascension Day were of going into the church for a service, when Mr Beckett would read the story of Jesus in the wilderness and the Ascension, from the large bible on the brass eagle. This always seemed very special to me.

Our entertainment was the concert at Christmas, for which we practised at Sunday School for many weeks before. I now realise how much patience our Sunday School teachers had with us. The Christmas Day Tea and Entertainment was at the Methodist School and the New Year’s Tea and Entertainment was at St Mary’s School. Both buildings were packed for these events. Then, on Whit Friday, St Mary’s used to walk through the village with the Band and we, the Methodist chapel, had our Field Day at Boardman’s Farm. The sun always seemed to shine, or do we never remember the rainy days?

My friends and I made camp fires in the plantation near Hawkshaw Farm, cooking potatoes etc, in old washed fruit cans. Didn’t they taste good! The health food fanatics would raise their hands in horror these days.

Two Brooks Mill was in full production in those days, complete with tennis court, bowling green and pavilion. The cloth was delivered by horse-drawn vehicle, and later on by steam engine. This mill, together with Kenyons and Bleaklow, made Hawkshaw a very thriving village and we are very fortunate that two of these mills are still in full production.

I hope that people of my generation will enjoy reading this article and recalling with me the “Good Old Days”. I hope also that the comparative newcomers to the village will also enjoy this brief insight into Hawkshaw in past days.”